PRESS

PRESS

NOEL FIELDING:

The comedian is returning to his first love - painting

The venue for his first exhibition? A cake shop, of course...

By Nicholas Barber

A few weeks ago, the first episode of the third series of The Mighty Boosh pulled in a million viewers, making it the most-watched programme in BBC3's history. The stars, Julian Barratt and Noel Fielding, were"really chuffed", says Fielding. "The BBC sent us champagne, and we went out and got absolutely wrecked." But a Little Britain-style promotion to BBC1 isn't likely, even if the duo's DVDs are bestsellers and their live tours sell out to fancily dressed students. "When I watch BBC1, I realise why we're not on it," reasons Fielding. "It's a pretty strange, quirky little show."

That's putting it mildly. The Mighty Boosh is a sort of sitcom that revolves around a classic sitcom act. Fielding, 34, bounces with Tiggerish enthusiasm, while Barratt, 39, is his crotchety, perpetually disappointed foil. Ratcheting up the laughs, Barratt and Fielding's characters go off on bizarre yet low-budget adventures to caves and desert islands populated by mermen and yetis. It's The Goodies as reimagined by Reeves & Mortimer, or vice versa.

The duo write the show, as well as providing songs and animation and designing weird creatures, some of which have Polo mints for eyes. Where does all this stuff come from?

In an effort to find out, I meet Fielding at a patisserie in Soho. He's not hard to spot. Like a technicolour version of his friend Russell Brand, he has a permanent grin, Mr Punch profile, and the shaggy hair and dress sense of the New York Dolls: this afternoon he's wearing a floppy black cowboy hat, long black coat, red Mighty Boosh T-shirt, tight polka-dot trousers and silver shoes. While Barratt is a publicity-shy family man, Fielding is an extrovert tabloid fixture who immediately starts talking about his mate Johnny Borrell from Razorlight, and about how Frank Zappa's daughter knitted him "this really long amazing cape". You don't interview him as much as dip a bucket into his burbling stream of consciousness. The only way he can relax, he says, is by painting.

As it happens, that's what we're here to discuss. Fielding's debut art exhibition is about to open in a room above the patisserie. "I know people want me to have an exhibition because they like the Boosh, but I decided it should in somewhere small, so the pressure wouldn't be so massive. I was thinking, maybe I should have done it anonymously. I was thinking of calling myself the Jelly Fox, and having some sort of armour on so no one would know who I was."

Fielding needn't worry. Judging by the few works already at the patisserie, and a few others he shows me on his cameraphone, one thing is obvious: the boy can paint. What's more, his offbeat, pop-art pictures are seriously commercial. They'd sell as fast as the patisserie's hot cakes whoever the artist was. The fact that it's a television star with famous friends will only bump up the prices.

Fielding always wanted to be a painter. He didn't get "sidetracked into comedy" until he was studying fine art at Croydon Art College, and had to create a performance piece based on a book. He chose the Bible. The piece began with Fielding hanging from a crucifix, and suitably sombre music playing. Then he leapt off the cross to "Jumpin' Jack Flash" and squirted holy water at his fellow students from a water pistol. "Everyone thought it was the funniest thing ever," he says, with chirpy honesty rather than arrogance, "so I thought maybe I should do some stand-up. I did my first three gigs in character as Jesus, because I didn't know whether I'd be funny as Noel. Then I thought, 'Jesus is a pretty powerful character, how am I going to follow that?'"

Encouraged by Harry Hill and Phill Jupitus, Fielding developed his own brand of fantastical rambling, and soon met Barratt, who liked to take off on similar flights of fancy. "I thought, this guy's very interesting and talented great performer, good music and pretty cool Julian went to drum'*'bass clubs, he knew about youth culture. When we found each other, we thought, we need to do something that will make our friends laugh cool people, people in bands. That's why we started our own comedy nights, because at that time Jongleurs was weird. People would be drunk and have a meal while watching you. They just wanted straight jokes. There was nothing there Julian and I could be part of."

In 1998, they went to the Edinburgh Fringe with a show that was different from everything else: an hour-long absurdist pantomime, with music, costumes and home-made props. They won the Perrier Best Newcomer Award. The following year, they were nominated for the main Perrier Award, and they've been exploring their own wonderland, and growing their audience, ever since. Next year, their tour includes a night at Wembley Arena, they're planning to do some TV in America, Mark Ronson has offered to produce their album and they have an idea for a film. Fielding is also a regular on Never Mind the Buzzcocks and The IT Crowd, but hopes to take a year off soon to focus on his painting. Which brings us back to the exhibition.

The paintings haven't been hung yet, so the gallery owner leads us to the basement where a few of them are stored. A friend of hers, the actor Bernard Hill, wants a sneak preview, too, so we process downstairs to a room cluttered with books and folders, with a red velvet couch against one wall, a stuffed toy deer propped on a shelf and a washing-line draped with chefs' uniforms hanging at eye level. The manageress picks up one of Fielding's paintings, which features a crocodile in a hat shouting "Show me the money!" Stylistically, it's somewhere between Henri Rousseau and Tove Jansson, creator of the Moomins. "There's a story to this one," Fielding says. "It's like a psychedelic Jungle Book." Then a glazier knocks on the door.

Somehow or other, then, we're in the basement of a cake shop between a minicab office and Jeffrey Bernard's favourite pub. The manageress is kneeling on a table, ducking under a washing line, holding a painting with one hand and shouting instructions at a glazier who's standing beside a cuddly Bambi, while a glam-rock comedian is telling one of the stars of Lord of the Rings about how a French documentary crew was filming the crocodile when it ate the director and stole his hat. So that's where all this stuff comes from. The Mighty Boosh don't make it up. It actually happens to them.

Fielding's work will show at Gallery Maison Bertaux, 28 Greek Street, London W1 (020 7437 8382), from 13 December to 29 February

Wake up and see the comedy

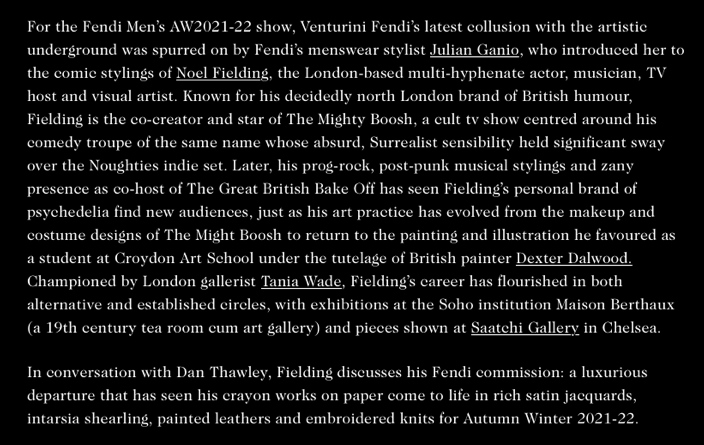

Visual arts PAINTINGS BY NOEL FIELDING

Photo captions: Expressionistic exuberance: Noel Fielding's 'Man With Cat'

Maison Bertaux LONDON HH Where would you go to find some physical manifestations of one half of The Mighty Boosh (the Noel Fielding half, that is)? Well, this morning I'm standing on the streets of Soho - in Greek Street, to be precise - diagonally opposite the theatre where Mary Poppins is still timelessly persuading us from a billboard, skipping towards us as she always does, and tricked out in that deathless smile of hers, that "anything can happen if you really let it".

Pushing past a couple of heavy, and heavily accented, men in donkey jackets who are delivering beer, I try to let it all happen. Huge yellow cans of Greek peppers and packs of sugar are being heaved out of a van by the ton just beside me, and I'm careful not to slip on the pavement either, which has just had its overnight vomit sluiced away from the doorway.

I enter the tiny and wholly delightful atmosphere of the Maison Bertaux patisserie where, having had a croissant and a café latte pushed into my cold, welcoming hands, I am being encouraged to mount the stairs to view paintings - new and not so new by, yes, Noel Fielding. Did you know that Fielding was a painter as well as a comedian? Nor did I. And he's no rank amateur.

The previous night, at the private view, his many fans included staff from Croydon College of Art where he trained some years ago - he's 34 now. The mob eager to buy included Dexter Dalwood, one of his former teachers, who is now a starring member of the Gagosian stable.

The paintings are everywhere, tiny, medium and large, riotously arranged, and spreading like stains, on stairs, in the loo, and in the café that overlooks the street. Even if the paintings weren't being displayed on almost every available bit of wall - there must be between 50 and 60 works in here - the room would still look festively heavy thanks to the giant red paper teardrop that hangs from the centre of the ceiling, and the streams of decorations that swing from one top edge of the room to the other like the rigging of some ship.

Just inside the door, gallerist Tania Wade, a touch bleary-eyed from having stayed up partying all night, sits at a desk nursing her own latte, and generally managing and talking to the many fans who keep drifting in to share their stories about Noel on Friday Night with Jonathan Ross, Noel sighted with Russell Brand, etc. There's piped music in the air too - the schmoozing of Billie Holiday getting through yet another long evening.

The paintings themselves are, well, full of a kind of expressionistic exuberance, riotously, if not violently, colourful, full of jokes and general, unhinged waggery of the Fielding kind. He's not only done paintings of some of his heroes in oils. The Ramones are here, as is Elvis, Bryan Ferry, and Mick the lips. He's also painted images on to ceramic and even paper plates.

The images on the plates are skulls for the most part. He is especially fond of skulls with huge circles of colour rimming their eye sockets. Another favourite theme is devilry. There are many diabolical imps here, sometimes flourishing full heads of antlers, which playfully, balefully prey on unsuspecting nudes in silhouette, caught stripping off in their windows. A crocodile in an orange hat and a stripy jumper rears up out of a swamp shouting: "show me the money!" Just then I hear Wade telling a punter about the prices. "They go from £360 for a skull plate to £8,000 for a large oil. He's happy to accept commissions," she adds helpfully.

Noel hasn't been able to resist spinning yarns in felt-tip pen on the wall, either (he was busy writing them yesterday evening, Wade tells me) which drift along serendipi-tously like dream narratives from some children's book. I start reading one: "When I first met BOOMBACLART the crocodile..."

Outside there's such a cacophony that someone - some merry drunk maybe - must think it's nearly Christmas.

MICHAEL GLOVER To 29 February

Thanks for inviting us - whoever you think we are

A LONDON LIFE CHRISTINA MADDEN

REALLY, I'm no namedropper.

But this week I found myself rubbing shoulders with some of the most famous people in the land — as an accidental invitee to a brace of celebrity parties.

The experience hovered between thrilling, alarming and frankly surreal. I racked my brain: why on earth was I invited to Shirley Bassey's 70th birthday party? My nominated plus-one was similarly nonplussed, and as we set off for Cliveden we agreed to treat it as an elaborate hoax until proved otherwise.

It wasn't till our cab was cruising the reassuringly long drive at the Astors' pile, past the parked-up helicopters, that I started to believe ... Along the red carpet (thank heavens for the beautiful fur coat and couture frock I'd scored in Barnardo's), past the circus artistes doing ethereal spindly things, into the great hall and (practically) into Joan Collins ... Two glasses of champagne in quick succession helped steady the nerves. We stood by a fireplace the size of my kitchen, mouthing: "Tony Christie!" "Honor Blackman!" "Is that Bruce Forsyth?" "What's Rolf Harris doing here?" Or, indeed, Raine Spencer, Siouxsie Sioux ... but mostly, us? Shirley descended the huge staircase to fanfares, flanked by semi-naked models, and sang Happy Birthday to Me to this "gathering of wonderful friends". The dancefloor soon filled with Valentino dowagers, all huge hair and even huger jewels, and I was doing the Time Warp alongside Cilla and Biggins, to a playlist that — if joyfully received — was fairly executive wedding disco. It reminded me of a Royal Variety Show circa 1981, or even (given Joan and multiple oil-baron lookalikes) a classic Dynasty episode.

Bemusement remained the order of the day, specially after learning the bash had cost a cool quarter-mil.

The other end of my week's celebrity curve could not have been more different: cult comedy charmer Noel Fielding's art preview, hosted by fabulous Soho gallerista Tania Wade at Maison Bertaux. Forget Cliveden's ranked coppers — security consisted of Tania's sister, and the guest list was scrawled on an envelope. All the hep young cats were there: outside, six-deep on the pavement, desperate for a glimpse of Noel's psychedelic-Jungle- Book paintings.

This was the maddest, coolest party of the year (my invite another mystery); the crowd a mash-up of Camden scenesters in eyeliner and wonky haircuts, mates like Johnny Borrell, Vic Reeves and the beautiful Dee Plume, Alexander McQueen, the odd Babyshambler — and Noel's mum and dad (in feather boa and parka, respectively). And me.

While Cliveden's arch, old-school "decadence" impressed, this was riotous, egalitarian good fun. But a million thanks to you both, Dame Shirley and Ms Wade. It was a week when I felt I'd slipped into someone else's, more glamorous, life. And you're always welcome round mine!

A new brush with the Boosh

PREVIEW

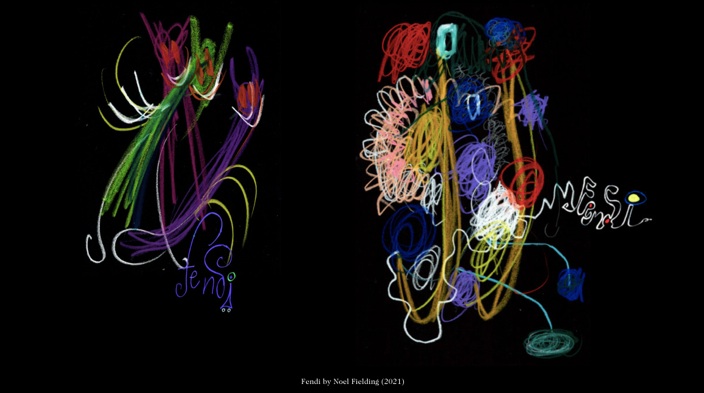

RICHARD GODWIN

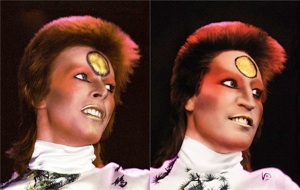

Photo captions: Exhibitionist at work: Noel Fielding in artistic mode as photographed by Nobby Clark for their collaborative show which opens tonight

Nobby Clark Shoots Noel Fielding Gallery Maison Bertaux, W1

COMEDY being the new rock 'n' roll is an old chestnut and one that's not very funny if you're a sorry stand-up getting heckled at a working men's club in Bridlington.

However, for as strikingly handsome and weird-headed a star as Noel Fielding, it certainly has rock 'n' roll benefits. The hard-partying, groupie-enjoying Mighty Boosh star is to commit the ultimate rock 'n' roll act of largesse as he and collaborator Julian Barratt become the first comedy act to put on their own festival.

The day- long Mighty Boosh festival, organised in collraboration with Vince Power of Mean Fiddler, will entertain 30,000 fans at Hop Farm in Kent on 5 July, with Fielding and Barratt topping a bill of their comical and musical mates. The full line-up is yet to be announced, but such is the fervour that the Boosh's surreal japery inspires, it is likely to sell out fast.

"We've never played a music festival before and a comic has never headlined a festival before, so we are seizing the opportunity and doing both," says Fielding. Perhaps Glastonbury — which is still having trouble shifting tickets — should take note.

In the meantime, not content with stealing the thunder from musicians, Fielding is taking more steps into the world of commercial art.

His paintings are the focus of a collaborative exhibition with the veteran celebrity photographer Nobby Clark, which opens tonight at Tania Wade's gallery-cum-patisserie in Soho..

Fielding's visual art is not a million miles away from the disturbing world of Nabootique he and Barratt create in the Mighty Boosh and it's no surprise that his depictions of talking crocodiles, Mick Jagger and disturbing fox-men — Matt Groening meets Hieronymus Bosch — have become highly prized collectibles.

For this exhibition, which launches with a suitably A-list-spangled party tonight, Clark has photographed Fielding at his easel. "It's the only way I can relax," he says.

Nobby Clark Shoots Noel Fielding is at Gallery Maison FOR MORE REVIEWS thisislondon.co.uk reviews Bertaux, 28 Greek Street, W1. Open daily 8.30am-11pm.

René Magritte: enigmatic master of the impossible dream

On the eve of a major Magritte exhibition, artists with an eye for the peculiar reveal why they love the witty Belgian surrealist

-

2The Observer, Sunday 19 June 2011

Magritte, Rene' (1898-1967): The Lovers, 1928. New York, Museum of Modern Art Photograph: Tate/DACS

TERRY GILLIAM Film director and former member of Monty Python

It wasn't until I'd seen Magritte's work collected together in an exhibition at the Tate, at the end of the 1960s I think, that I realised just how incredibly funny his stuff was. People walk around these exhibitions in a religious state of awe and I just walked round this one laughing uncontrollably. Until then, I'd always thought of Magritte as having an interesting and intriguing mind – the way he would turn things inside out or make that which was solid suddenly not solid. But suddenly here he was, this wonderfully dry joke teller. The work that really struck me that day was The Man in the Bowler Hat [1964]. He'd spent months painting a guy in a bowler hat and then, for his last brush strokes, paints a dove flying in front of the man's face. What's happened there could happen only in a photograph and he's done a painting of it. What a comedian! I thought he was so clever. If it wasn't for the ideas I wouldn't say he was a great painter because others have a better technique. But he does what he needs to do and does it so well.

All of the surrealists got into my head, but Magritte was so direct. I liked how immediate his work was, whereas the others were more abstract. His work can be complex but in a sense he takes cliché images and puts them together in ways that surprise you. There's a night scene, but the sky is day [The Dominion of Light, 1953], there's a pair of shoes that are actually feet [The Red Model, 1934]. His work has an initial gag, but the stuff sticks with you because it's in some ways profound.

He is so firmly lodged in my brain that frequently I'll see something and think, "Oh, that's a bit Magrittean". I'll look out of my window at dusk and see the house across the street catching the last bit of sunlight, except the sky behind it is already night. He captures moments of light in the day that are just odd. I used to think it was a fantasy of his, but I now find it happening all the time. Like every good artist, he makes us see the everyday differently but he does it without the pretension of so many other artists. That's another thing I like about him, that he didn't have this serious "I am an artist" approach. He went to work with a suit and a briefcase, everything about him was taking the piss out of art yet at the same time he was a wonderful artist.

In my work, I can never find a direct line between what I've done and where it's come from, but I do know where the influences are and they all end up in a kind of Irish stew in my brain. I would never want to say: "I nicked that from Magritte", because that's criminal investigation time! But it would be fair to say that with the landscapes and blue skies in the Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus I could've been stealing from either Magritte or Microsoft Windows. What Microsoft did was a direct steal from Magritte! Other people paint more elaborate skies, but it's the clarity of his painting – the perfect blue sky with the perfect clouds floating in it – that's just so appealing.

Were the other Pythons influenced by Magritte? No. I'm not sure what the word is for being illiterate at art. Maybe blind. That's what they were. Years ago, we were in a hotel in Munich and John [Cleese] called me and said: "I'm going over to the Pinakothek. Do you want to come and explain art to me?" So I went along and I didn't explain art to him because that's not what I do, but I did get him looking at a thermostat on the wall and discussing it in great detail. We managed to gather quite a crowd.

I suppose with my work I'm always trying to get people to see what the world is capable of, to show how it can be seen in a very different way and Magritte did that all the time. When you start thinking differently like that, reality becomes a kind of game. In the 60s, people took drugs to achieve that state, but for a lot of people it was enough to go and look at a Magritte painting.

JEFF KOONS Artist

Whenever I drive in any mountainous region and look at the line against the sky, I think of Magritte. And whenever I see beautiful, perfect clouds in the sky, he's the first thing that comes to mind. I think there is a humanity, a generosity and a kindness to others in Magritte's work. He takes the viewer into account. And I have always found the economy of his images very moving. They communicate very purely and directly. One of the most profound pieces of Magritte's is Discovery [1928]. It is an image of a woman whose flesh resembles the grain in wood. There is this aspect of Magritte which is about dealing with the world around us, and there is a certain materiality, a reality about that world that he creates, even though he makes these strange juxtapositions.

It is hard to imagine a lot of the computer programs that we work with in daily life, such as Photoshop, without the influence of Magritte. We owe to Magritte the many ways that we see the world through transparency or gradation. So I hold him in high esteem for showing us how images can be overlapped, or how they can be gradated into each other. I wouldn't say I've ever made a piece in direct response to his work, but I can see there are works that show an interest in what he was doing. Take Les Idées Claires [1955], one of the two Magritte paintings that I have loaned to the Tate exhibition. Here, you see a rock hovering over the ocean underneath a cloud. I can associate that with one of my Equilibrium Tank sculptures of basketballs suspended in vitrines of water.

© This is an edited extract from Tate ETC magazine

NOEL FIELDING Artist and co-creator of The Mighty Boosh

I love how Magritte's paintings initially look quite normal. He lures you in with the colours and compositions and shortly after the concept blows your mind. You think: "That's just a normal… aagh!" They're like Trojan horses.

I've still got the first book I had of Magritte's work. It's stolen from the library, that's so bad! I was about 12 years old and looking at the paintings was a bit like taking drugs. They're such strong, stimulating images for a child because at that age you don't drink, you don't take drugs and you're not really interested in girls.

The first painting that made me think, "Oh my god, that's something amazing" was Young Girl Eating a Bird [1927]. I liked how enigmatic Magritte's work was, how you didn't quite know what was going on. Surrealism and absurdity, Monty Python and Vic Reeves, they were the first things that I really buzzed off and thought, "wow, that's what I want to do". The fact that there was a surrealist movement really appealed to me too, that they met up and drank crème de menthe in weird Parisian cafes. I loved that these grown men like Breton and Magritte would really seriously discuss poems, automatic writing and painting and then put things in their magazines like a man throwing a rock at a priest. I guess it was quite punk at the time.

Magritte's paintings always make me laugh. I don't care if other people say they're not funny. I find it ridiculous when you walk around a gallery and people are just looking at something obviously funny and stroking their chins. A Magritte painting such as the reverse mermaid [Collective Invention, 1934] is like a stand-up joke. Comedians do those reverse jokes all the time. When I was quite young, I did a painting of a cat phoning the fire brigade and an old lady stuck up a tree.

It's the juxtaposition in the paintings that is also very stimulating. I think it was Terry Jones who said something about two disparate ideas coming together and creating a star. And that's what it's all about for me. In The Mighty Boosh, we have a character called Old Gregg who is a merman but he's also a bit like [musician] Rick James. Those two things shouldn't ever go together. But when you get it right it's perfect.

Some of my own paintings are definitely influenced by Magritte. The stillness and the weirdness of Bryan Ferry with a Kite, in which Bryan Ferry has got a kite for a head, that's one of them. But he was also one of mine and Julian Barratt's joint favourites and that's apparent in the Boosh. For ages, we even wanted to have a pipe as an actual character who floated around and talked. But it was too difficult. You can see from what Julian wears that he likes the whole Magritte aesthetic – the bowler hats, the trench coats and the weird city-gent-gone-wrong look. Together, lookswise, we're like Dalí and Magritte. Dalí was more my type: flamboyant, a mad freak.

My new show for E4 has even more references to art. It's set in a place that's supposed to be my house, I look like a Bollywood Elvis and my cleaner is a robotic Andy Warhol. At one point, Warhol borrows a rucksack from Magritte to go on holiday with Jackson Pollock and Keith Haring and when he turns around a train comes out of the rucksack, like the train coming out of the fireplace in Time Transfixed [1938].I say to Warhol: "I bet that gets a bit annoying", and he responds, in his robotic voice: "No, you can get loads in there."

Magritte's paintings are insane, but they're often really good one-liners so they're a great source for a surreal comedy show.

ALICE ANDERSON Artist

When Magritte was 13, his mother committed suicide and, apparently, when the police retrieved her body from the river Sambre, Magritte was there and he saw how her face was covered by her dress. My own art and the research I do around it is all about neuroscience, how brains function, how memory functions, so this episode in Magritte's life and the way it subsequently influenced his art really intrigues me. If you look at The Lovers [1928], where two people have clothes over their face, I think that work specifically draws on that episode with his mother. But more generally, his work explores memory, his funny perception of reality and for me that all comes from his memory of that event. In Le Blanc-Seing [1965], for example, which features a woman on a horse in a wood, there are almost two paintings. The way his paintings constantly shift between what is real, something he can see or saw, and something he really wants to see is what draws me into his work.

GAVIN TURK Artist

One of the great things about Magritte's work, especially The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe) [1921] is it dismantles the idea of pictures themselves. It makes the audience consider what they're looking at and take a step back. You can see that Magritte painted to experiment with his own thinking. His work is a thinking through pictures. I probably first came across the work when I was on my art foundation course and I remember my sense of relief to find that his work was immediately gettable. Some people today don't identify with the themes he's exploring or perhaps can't see past the cliché. But the way he suggestively starts to make the audience question how they see things is something that I try to include in my own art.

There are two works of Magritte's which I've more or less directly appropriated in my works Oscar and Cripple. They are The Ellipsis [1948] and The Cripple [1948], from his vache period, when he started painting more loosely, almost in a semi-expressionistic style. This period was a disaster for Magritte: the critics panned the work and the collectors ran away. But I love that he was fed up with being expected to be a certain kind of artist and was challenging his signature style. This new style almost allowed the audience in slightly closer, to get more of an insight into Magritte himself. I made two sculptures, three dimensional self-portraits, that were then reconfigured to look like these two paintings by Magritte. I was dealing with the idea of my own personal representation, my own ideas of authorship.

I also like the happy oddness, the sense of the uncanny in Magritte's work. In a way, there's a non-threatening but uncomfortable sensation. In an era before Photoshop, he slammed together things from different worlds and played with scale. If I were to draw parallels between his work and mine it would be that we combine disparate ideas or use this sense of the uncanny to make proposed alternatives. A work of mine like the bronze binbag sculpture is a good example – it seems straightforward, it's a shiny binbag, but then it starts to make you ask questions. It's a painted bronze sculpture, so there's this sense of permanence when actually a black plastic bag is probably a key symbol of impermanence.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/jun/19/rene-magritte-surrealist-favourites-tate/print

Glam Photoshoot - http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/gallery/2013/feb/01/noel-fielding-recreates-classic-glam-images

Additional Press:

WRITE UPS AND MOVIES

http://www.i-donline.com/i-spy/noel-fielding-part-one

http://www.i-donline.com/i-spy/noel-fielding-part-two

http://www.bizarremag.com/entertainment/interviews/9988/noel_fielding.html

http://www.bizarremag.com/entertainment/interviews/9880/noel_fielding.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/sep/19/noel-fielding-boosh-interview

http://www.nme.com/news/the-mighty-boosh/53633

http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2010/jun/27/noel-fielding-maison-bertaux-ferry

VELVET ONION ARTICLES

http://thevelvetonion.com/2010/07/05/a-playground-for-eyes-and-mind/

http://thevelvetonion.com/2010/10/01/tania-wade-west-end-girl/

http://thevelvetonion.com/2010/10/08/the-art-of-fielding/

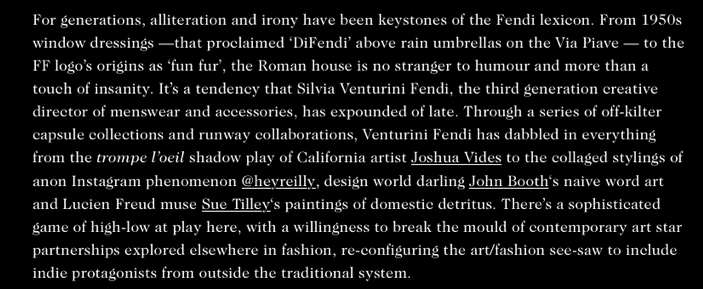

Full article: https://amagazinecuratedby.com/curatedfor/fendi-noelfielding-mightyboosh-artbrut/ (2021)